Printed in the May 2010 issue of SwissNews

“In French it means “hobby horse”. In German it means “good-bye”, “Get off my back”, “Be seeing you sometime”. In Romanian: “Yes, indeed, you are right, that’s it. But of course, yes, definitely, right”….The word, gentlemen, is a public concern of the first importance.” -From the dada manifesto read by Hugo Ball at the first public Dada event on July 14, 1916

And with that declaration, Hugo Ball launched one of the most influential and important (anti-) art actions of all time, Dada.

Zurich of 1916 was the gathering place for refugees from war-torn Europe, a place where people came to find peace and stability. It was also a relatively permissive environment that had a history of accepting the revolutionary ideas of Europe’s disillusioned intellectuals, including Lenin who was preparing his own revolution in 1916. Therefore, it’s no surprise that artists, political activists, intellectuals, and regular citizens weary of the fighting and death in their native lands swarmed to Zurich, getting together at bars and cafes, planning new revolutions (political and otherwise) and discussing till all hours of the night the “future society”.

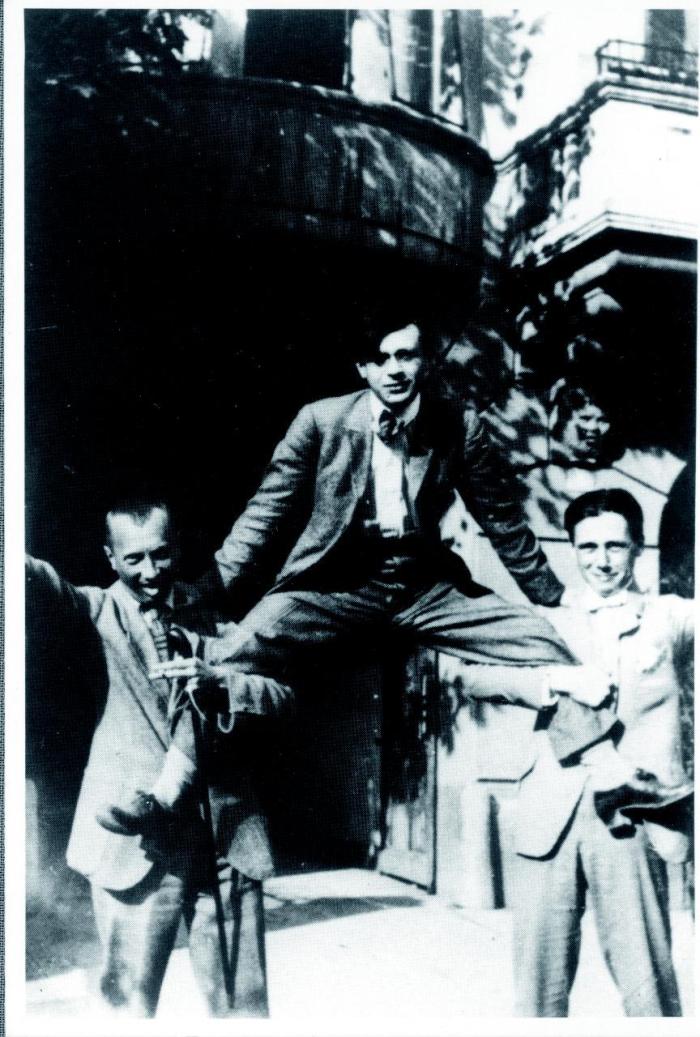

Among these refugees were Hugo Ball, his soon-to-be wife, Emmy Hemmings, Tristan Tzara, the Janco brothers, (Marcel, George, and Jules), Arthur Segal, Jean Arp, and Richard Huelsenbeck, the future founders of Dada and its home, the Cabaret Voltaire. Many of the group’s original members were Romanian Jews escaping the ultranationalist and anti-Semitic tendencies rapidly taking shape in Romania, while others were Germans escaping the war. They were united by their conviction that the horrors around them, the death and destruction, were rooted in outdated bourgeois values that still governed Europe, and that that societal order, with its inequalities and brutality, needed to be destroyed for another, more human, to be created.

And it was with this desire to destroy accepted values and tradition that Hugo Ball went to the owner of a bar in the old town of Zurich, the Hollandische Meierei, to ask its owner, Ephraim Jan, for the back room, to be used for a new project: a cabaret with singing, theatrics, music, visual art exhibitions, and all sorts of other performances that would disturb bourgeois sensibilities. It was called the Cabaret Voltaire after the French philosopher who once had also challenged the status quo with his enlightened ideals, it opened for the first time on February 5, 1916.

This first event was not much different from the cabarets or soirees that Ball had organized before in Berlin. Most artists involved came from an expressionist or futurist background, while the music was relatively tame and mainstream in those modern art circles. But with time, the performances became more and more daring, pushing the limits of respectability to the ultimate climax on July 14, 1916, when the first soiree essentially dada took place.

Most of these artists, specifically Ball, Tzara, the Janco brothers, and Huelsenbeck, were well read in contemporary political theory, and sympathized with anarchic ideals. Hugo Ball was a great admirer of the Russian anarchy theorist Mikhail Bakunin, who had also spent time in Zurich , but a few decades earlier in the 1870s.

Influenced by Bakunin’s ideas, Ball and his friends started to apply his theories, which Ball considered “to be Dada in political disguise”[1], to their new mode of art creation, whose name they also conceived anarchically, by chance. The legend goes that the name for what they were doing was adopted by randomly sticking a knife into a dictionary and finding under the blade the noun dada, hobby-horse in French. Conveniently enough, the name also means “yeah, yeah” in Romanian, or “yeah, right”, an obvious slap in the face to the tradition of “isms” epitomizing theory, order, and reason in the early 20th century. Once dada became an international phenomenon, with adherents in all major world cities, artists started debating the origin of the name, claiming it as their own finding.

In the introduction to the first and only issue of the publication called the Cabaret Voltaire, where the idea of dada first appeared formally at the end of May 1916, Ball wrote a humorous account of the process of launching the cabaret, “When I founded the Cabaret Voltaire, I was of the opinion that there ought to be a few young people in Switzerland who not only laid stress, as I did, on enjoying their independence, but also wished to proclaim it. I went to Mr. Ephraim, the owner of the “Meierei” restaurant and said, ‘Please, Mr. Ephraim, let me have your hall. I want to make a cabaret.’ Mr. Ephraim agreed. So I went to some friends of mine and asked them, ‘Please, let me have a picture, a drawing, an engraving. I want to have an exhibition to go with my cabaret.’ And I went to the friendly press of Zürich and said, ‘Write a few notes. It shall be an international cabaret. We want to do some beautiful things.’ And they gave me pictures, and they wrote the notes. … It is to exemplify the activities and the interests of the cabaret, whose whole endeavour is directed at reminding the world, across the war and various fatherlands, of those few independent spirits that live for other ideals. The next aim of the artists united here is to publish an international periodical. This will appear at Zürich and will be called ‘DADA Dada Dada Dada Dada.’”

Unfortunately, the cabaret soon closed in June 1916, but dada was just beginning. The Dadaists, despite an internal conflict brewing among them, rented a room for one night at the Waag Hall and there they held the historic July 14 Dada Soiree, which officially launched dada with Ball’s first version of the manifesto (anti-manifesto), Tzara reading his own manifesto, Huelsenbeck reading his phonetic poem, more wild performances, absurdist literary readings, avantgardist works of art, and general chaos. Every gesture and every move was calculated for the most impact and shock in the audience, thus ensuring the group’s aim of destruction and negation of acceptability, aesthetic, and reason. If art until then had been based on aesthetic, then dada was anti-art, and these performances were hideous and disturbing, like the war around them.

After the closing of the Cabaret Voltaire when Mr. Jan could no longer take the madness, the artists associated with dada moved on, first hosting regular exhibitions at Galerie Dada in Bahnhofstr 19, which also closed soon thereafter in June 1917, then to other cities bringing dada ideas with them and establishing local dada branches. Those that didn’t remain Dadaists went on to create great work in other movements, particularly Surrealism. However, Hugo Ball, who actually separated himself from Dada in early 1920, turned to Christianity and retired to Ticino until his death. Tzara went on to establishing the Dada school of thought and become its main promoter and leader.

Since its closing in 1916, the building housing the Cabaret Voltaire on Spiegelgasse 1 has gone through many transformations. In 1989, the space was a Teen ‘n’ Twenty disco, with only a plaque with the word dadaismus on the building, commemorating the cultural revolution’s origins. But in 2002, while the building’s owner was considering turning it into offices, a group of artists, among whom Mark Divo, a conceptual artist now living in Prague, squatted the building and started a series of dada performances and festivals to raise awareness of its history and importance.

The excitement generated by these events were noticed by Swatch CEO Nick Hayek, and along with the Zurich City Social-Democratic Party and architecture magazine “Hochparterre”, petitioned the city government to open an arts center dedicated to dada at the location. Swatch promised a few million francs in funding over a five-year period, with the expectation to sell its dada watches in the center’s shop.

And thus, in 2004, Cabaret Voltaire, funded by the city of Zurich and private funders, opened its doors as an institution. What would have thought the fanatically anti-establishment dadaists about this institution dedicated to what cannot be institutionalized? In one of his letters to Tristan Tzara after his break with Dada’s direction under Tzara’s leadership, Hugo Ball, the original co-founder of the movement wrote, “I have another system now. I want to do it differently….I declare hereby that Expressionism, Dadaism and other “isms” are the worst type of bourgeoisie. All are bourgeoisie, all bourgeoisie. Evil, evil, evil” (Ball, Briefe, September 15, 1916, p 62-63).

Very, very interesting and I liked the many photos!

The website http://www.dadart.com would like to make a link (in its English version) to this well-written, well-documented, well-illustrated page if you agree.

Best,

Gilda Fine

Pingback: 1 | SDES-1304 Making do, textiles.

Pingback: Cabaret Voltaire « dadadadadadadada

Pingback: Total war or total trivialisation? Cultural intermediation, translation and practice. | Cultural intermediation & the creative economy

Pingback: 5 January h 19.15-100 years of DADA | EYE on Art